A Digitally Controlled, Remotely Operated ICSI System: Case Report of the First Live Birth

Cohen et al., Reproductive BioMedicine Online (RMBO), 2025

Table Of ContentsIntroduction

Materials and Methods

Results

Discussion

Acknowledgements

Highlights

Automating the entire micromanipulation element of intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI).

Enabling remote control and supervision of ICSI.

ICSI was performed by a remote operator 3700 km away.

First live birth following fertilization by remote ICSI.

Abstract

Research questionCan a fully automated, digitally controlled, remotely operated system execute the entire micromanipulation process of intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI)?

DesignA workstation automating the 23 micromanipulation steps of ICSI was engineered. The system operated independently under artificial intelligence control or under digital control executed by a remote operator. Pre-clinical validation was conducted with animal models to ensure safety and efficacy. In a clinical application, five donor oocytes intended for the treatment of a 40-year-old patient were fertilized using the automated ICSI system under remote supervision; three additional oocytes were injected manually as controls. Elective single embryo transfers were performed.

ResultsThe automated ICSI system achieved an 80% fertilization rate (n = 4/5), comparable with the manual controls (100%, n = 3/3). Two usable blastocysts were generated in each group. A fresh embryo transfer using an experimental embryo did not result in pregnancy. However, the transfer of a warmed blastocyst from the automated ICSI group resulted in a healthy live birth at 38 weeks of gestation. The system completed 49.6% of the required 115 micromanipulation steps (23 per oocyte) autonomously, and the remaining steps were conducted under digital control by the remote operator. The average time for automated injection of an oocyte was 9 min and 56 s. On-site human intervention was required for the initial set-up, and was needed on one occasion for troubleshooting one of the automated steps.

ConclusionsThis study demonstrates the feasibility of fully automated, remotely operated ICSI achieving a live birth. While improvements in autonomy and efficiency are needed, this milestone highlights the potential for automated systems to transform assisted reproductive technology practices globally, enhancing accessibility and standardization.

KEY WORDSIntroduction

The success of current assisted reproductive technology (ART) relies heavily on the expertise and performance of embryologists. Achieving this level of expertise requires extensive training and practice, which can vary significantly between individuals. Additionally, performance can fluctuate daily, influenced by factors such as fatigue and stress (Murphy et al., 2024). Automation of the fertility laboratory represents a transformative solution that promises to enhance precision, improve efficiency and ensure consistent outcomes, while reducing variability and work-related stress on human operators (Abdullah et al., 2023). The pathway to full automation will require the digitalization of many individual processes which are currently performed manually. Furthermore, automated systems should be designed to allow for human supervision, including remote monitoring, quality assurance, troubleshooting and management of unusual cases.

Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) is a common yet complicated approach used to fertilize human oocytes in ART. Thus, the development of a digitally controlled, remotely operated ICSI workstation could serve as a cornerstone in the path towards full laboratory automation.

Since its successful clinical application in 1992 (Palermo, 1992), ICSI has not seen many technical changes, due in part to its success in achieving fertilization regardless of the sperm profile (Nagy, 1995). However, clinical outcomes are still operator dependent (Tiegs and Scott, 2020). Automating the process could not only lead to standardization but may also improve oocyte survival and optimize timing of injection.

The first attempts to automate ICSI were reported in 2011, describing automated sperm immobilization and utilizing the hamster oocyte/human sperm model to perform ICSI (Leung et al., 2010; Lu et al., 2011); the investigators reported that approximately 90% of the injected hamster oocytes survived. A microfluidic device intended to perform ICSI was patented in 2016, but its clinical application has not been reported (Palermo, 2016, US patent US9499778B2). More recently, Costa-Borges et al. (2023) reported the birth of two babies using a system that automated nearly 50% of the individual steps in ICSI (Alikani, 2023). Notably, steps such as sperm selection and immobilization were not automated in this robotic system.

This article reports the birth of the first child conceived through a digitally controlled, remotely operated ICSI workstation. The system was developed at Conceivable Life Sciences (New York, USA and Guadalajara, Mexico), automating, for the first time, all micromanipulation steps of the ICSI workflow. The system integrates mechanical and electronic engineering, incorporating automated turret and microscope stage control, and computer vision [first presented by Mendizabal-Ruiz et al. (2024a,b)]. It also employs artificial intelligence (AI) for sperm selection, laser technology for sperm immobilization, and piezo-actuated pulses for penetration of the oolemma.

The experimental treatment was performed at Hope IVF Mexico (Guadalajara, Mexico) as part of a pilot investigation into various aspects of the automation of fertility laboratories. This milestone represents a critical proof of concept, demonstrating that digital control and remote supervision of ICSI can be achieved, paving the way for further evaluation studies.

Materials and Methods

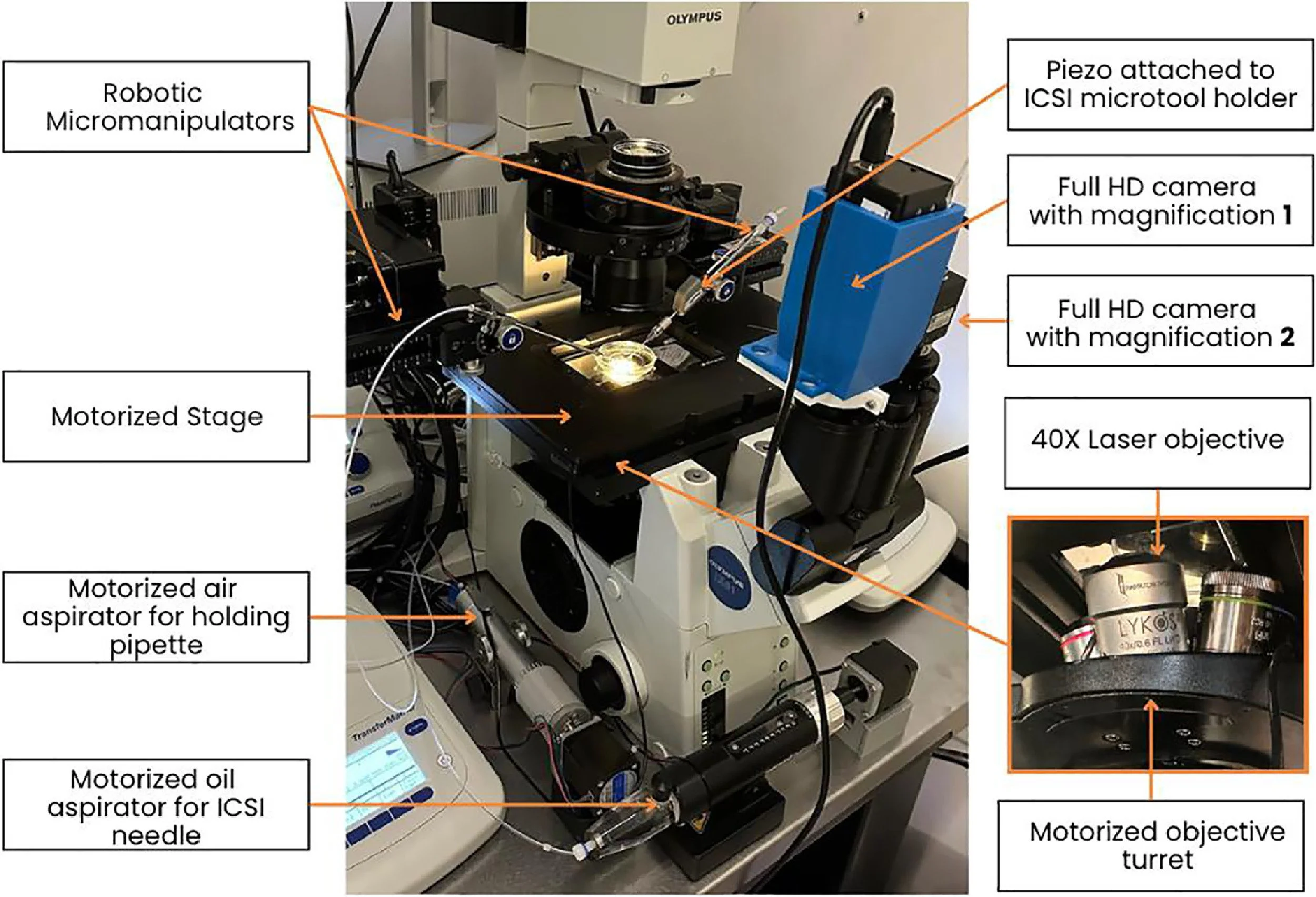

Development of the automated ICSI systemA remotely controlled, fully automated ICSI system was developed from off-the-shelf components including an inverted microscope (IX 81; Olympus, USA), a heated stage (Tokai Hit, Japan), a non-contact laser (Lykos DTS, USA), a piezo actuator (PiezoXpert; Eppendorf, Germany), a motorized stage (H117; Prior Scientific Instruments, UK), a motorized objective turret (U-D6BDREMC; Olympus), oil and air microinjectors (CellTram Oil, Eppendorf; Narishighe, Japan) and cameras (IMX477; Arducam, Hong Kong) to allow complete digital supervision (Figure 1). The system implements the principles of laser sperm immobilization (Ebner et al., 2001), laser-assisted ICSI (Abdelmassih et al., 2002; Verza et al., 2013) and piezo-ICSI (Zander-Fox et al., 2021). The previously developed ‘SiD’ AI (Mendizabal-Ruiz et al., 2022) was employed to select and track sperm cells. Additional custom-built software was used to segment cell types such as oocytes and spermatozoa, and microtools. Software was developed to automate key steps, including laser immobilization, sperm loading into the microneedle, oocyte localization and optical segmentation, guided sperm injection, and tracking with focus adjustment on gametes and microtools. Segmentation, in this context, refers to the process of labelling pixels that constitute a specific object, such as a cell. Here, the AI identifies pixels belonging to the spermatozoon and classifies them into ‘head and neck’ or ‘midpiece and tail’ based on their morphological structures. The system was engineered at a dedicated research and development facility (Conceivable Life Sciences, Guadalajara, Mexico).

Figure 1 The remote intracytoplasmic sperm injection experimental set-up, adapted from a standard micromanipulation workstation, modified to incorporate fully motorized and digitally controlled components for remote operation.

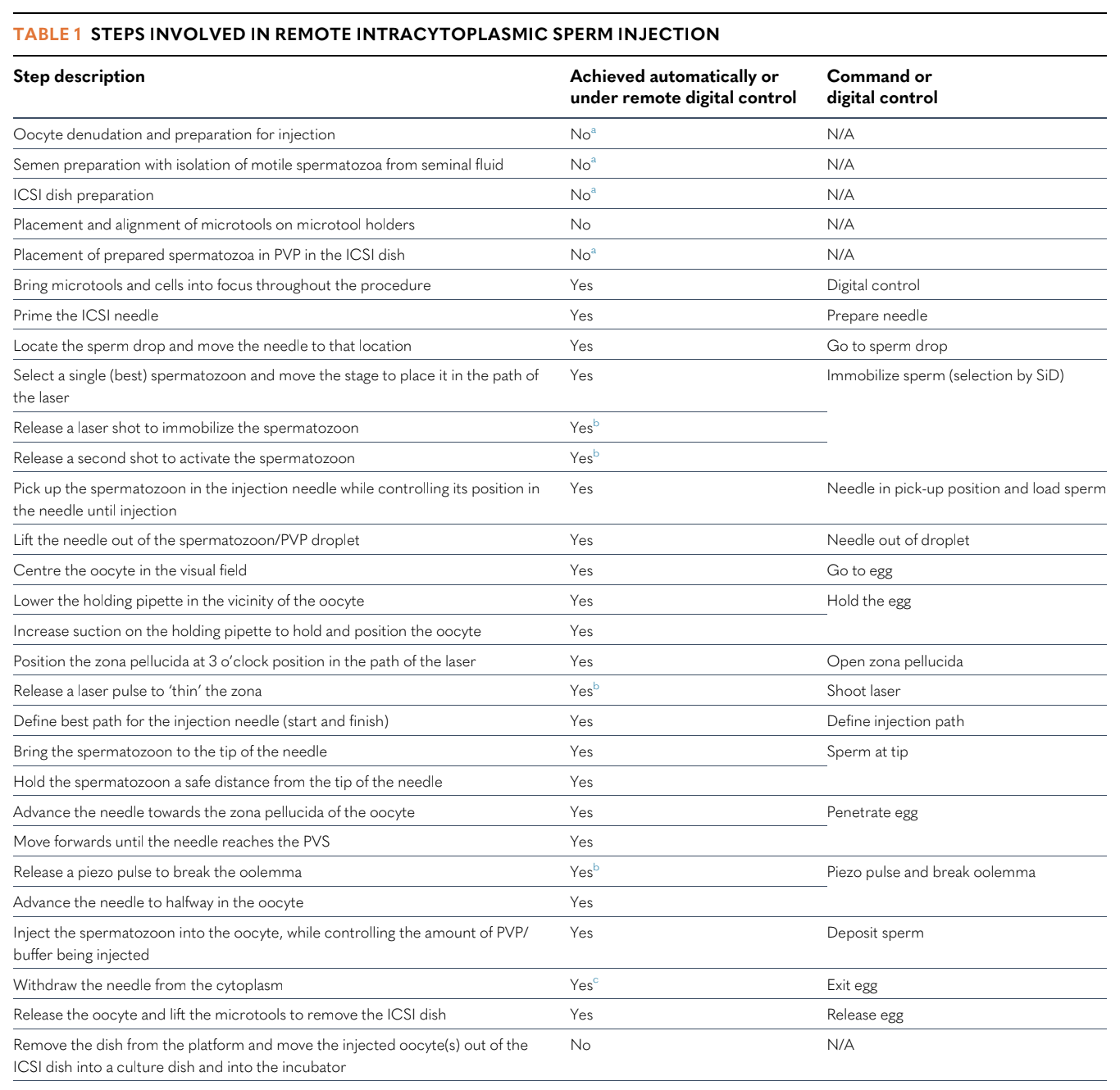

A description of the 23 steps performed by the automated ICSI system is given in Table 1. Individual commands corresponding to these steps could be issued via a computer-based interface either locally or from a distance (remotely). The operators did not need to interact directly with the micromanipulators or the microscope. However, initial set-up, sperm droplet preparation and positioning the oocytes in the ICSI dish (and later recovering the injected oocytes) was performed by an embryologist on site. The sequence of microscopic steps is illustrated in a video of the actual procedure (Supplemental Video 1). The injection utilized a standard holding needle and a standard bevelled microneedle (Cooper Surgical, USA).

Table 1

Steps involved in remote intracytoplasmic sperm injection

‘Automatic’ implies execution using a digital command issued remotely using a computer interface and a broadband connection with minimum upload/download speeds of 50 Mbps.

Although these steps were not automated in this study, the study group has achieved their automation through the employment of additional systems (Flores Saiffe Farías et al., 2024; Millan et al., 2024).

Commands, including ‘shoot laser’ and ‘piezo pulse’, are intended for human interaction/intervention with the user interface if necessary. On the user interface, controls are available for microtool movement, magnification level, microscope focusing, and incremental negative and positive pressure control in the holding pipette and ICSI needle.

The human operator only reacts if the spermatozoon is pulled back out by negative pressure in the needle. Exiting from the oocyte is a two-step process, with a pause to ensure that the spermatozoon is not pulled back out.

N/A, not applicable; PVP, polyvinylpyrrolidone; SiD, artificial intelligence for sperm selection (Mendizabal-Ruiz et al., 2022); PVS, peri-vitelline space.

Table adapted from Alikani (2023).

Artificial intelligenceSiD (Mendizabal-Ruiz et al. 2022) was employed for automated sperm cell selection. Software refinements enabled this AI to determine the trajectory of the highest-ranked spermatozoon within the field of view, command the motorized stage hardware to align the laser system to its mid-tail region, and activate a laser pulse to immobilize the spermatozoon. Once immobilized, a dedicated AI, developed in-house, segmented the spermatozoon and determined the positions of its head, the mid-point of its tail, and the tail tip. This facilitated precise alignment of the laser to the mid-tail for a second laser pulse, ensuring effective sperm immobilization. The tail tip position guided the placement of the ICSI needle for sperm loading. The position of the sperm head informed the system controlling the suction mechanism of the microinjector, allowing adjustment of positive or negative pressure to pick up and retain the spermatozoon inside the needle. Another in-house-developed AI specialized in identifying the oocyte under 4X and 40X objective magnification, and determining the positions for holding pipette alignment, laser thinning of the zona pellucida (laser-assisted ICSI), penetration by the injection needle, and sperm deposition in the oocyte. An additional custom-built AI tracked the locations of the ICSI microtools within the field of view of the microscope. The data were used to direct the micromanipulators for precise instrument positioning, such as directing the ICSI needle to the tail tip of the spermatozoon, directing the holding pipette to the external edge of the zona pellucida to hold the oocyte, and maintaining instrument alignment during injection. Finally, an AI was trained in-house to track the position of the spermatozoon within the injection needle, which was critical for stabilizing and positioning it during loading and injection. Examples of the operation of these AI are given in the supplementary video.

Pre-clinical validationValidation with animal models was conducted at Embryotools (Spain) to assess the feasibility and test the safety of the digitally controlled ICSI system. A mouse model was employed to identify the optimal settings for immobilizing spermatozoa permanently using a laser, and to evaluate the safety of this method. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software Inc., USA). Fertilization, blastocyst and live birth rates were compared between groups using chi-squared test with Bonferroni's correction for P-values. Statistical significance was set at 5% (α = 0.05). No differences in fertilization and blastocyst formation rates were found between mouse oocytes injected manually by piezo-ICSI with laser-immobilized spermatozoa (n = 176, 98.8% and 80.7%, respectively) and oocytes injected with control spermatozoa immobilized mechanically (n = 173, 99.4% and 80.6%, respectively) (chi-squared test, P = 0.57 and 0.93, respectively). The transfer of 94 blastocysts from the laser-immobilization group resulted in a 40.4% live birth rate, which was similar to the control group (n = 92, 47.8%) (chi-squared test, P = 0.31). All mice showed normal health, behaviour and fertility for two generations. Additionally, the performance of remote-operator ICSI was evaluated utilizing hamster oocytes and human spermatozoa to assess oocyte survival post-injection, following a previously described approach (Gvakharia et al., 2000). The remotely controlled system achieved an oocyte survival rate at 2 h post-injection of 94.1% (n = 102), which was similar to that of manually injected oocytes (n = 102, 97.1%) (Fisher's exact test, P = 0.50).

Pre-clinical validation experiments have been presented previously in conference proceedings (Costa-Borges et al., 2024; Mendizabal et al., 2024a,b). A complete description of this work is in preparation and will form part of a separate manuscript.

EthicsBefore the system was utilized in a clinical case, institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained from the Comité de ética en investigación New Hope Fertility Center (registration number with national IRB authority CONBIOÉTICA-09-CEI-001-20170131, approval reference RA-2023-01, approval date 22 September 2023). Conceivable Life Sciences sponsored the trial. Their staff members are not associated with the IRB. The IRB consists of seven independent members: three medical doctors, one embryologist, an independent academically affiliated president and two patient representatives. In Mexico, an IRB must be registered with Conbioetica, the Mexican national body for bioethics. Requirements of the research ethics board are similar to Food and Drug Administration requirements in the USA, including complete independence and annual reporting of the IRB to Conbioetica.

The study protocol was registered with Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT06074835). Written consent was obtained from patients. Treatment was conducted between December 2023 and February 2024.

Case presentationA 40-year-old woman with slightly elevated body mass index (25 kg/m2) presented with primary infertility and diminished ovarian reserve (anti-Müllerian hormone 0.1 ng/ml) seeking ART treatment with her partner, a 43-year-old male with moderate teratozoospermia (semen volume 2 ml, sperm concentration 18 M/ml, sperm motility 77%, progressive motility 66%, normal forms 2%). The couple was referred for ICSI treatment with donor oocytes at Hope IVF Mexico following a previously failed IVF attempt, where ovarian stimulation produced only one mature oocyte and no embryos.

Ovarian stimulation, oocyte retrieval and sperm preparationThe oocyte donor was a 23-year-old woman who underwent ovarian stimulation with gonadotrophins (Gonal-F; Merck Serono, Germany) over 9 days; her blood oestradiol concentration on the day of trigger was 1117 pg/ml. The patient was triggered with a gonadotrophin-releasing hormone agonist, Gonapeptyl (Ferring, Switzerland). Ultrasound-guided oocyte retrieval recovered eight mature oocytes (plus six immature oocytes; three other oocytes were atretic). The mature oocytes were vitrified and subsequently warmed for patient treatment following the standard Cryotop approach (Kitazato, Japan). Fresh spermatozoa were collected by the patient's partner at the treatment site, and prepared by standard density gradient centrifugation (ISolate sperm separation kit and Multipurpose Handling Media supplemented with 5% HSA; Irvine Scientific, USA), followed by an additional swim-up step for use in ICSI.

Remote ICSI procedure, embryo culture and fresh embryo transferAll metaphase II oocytes were placed in a single droplet. To ensure random selection, the image in the stereoscope was blurred intentionally, and an embryologist allocated the oocytes at random to either the experimental remote ICSI group (n = 5) or the manual control group (n = 3). The conventional ICSI procedure was described previously (Mendizabal-Ruiz et al., 2022). This approach did not involve piezo for zona penetration, laser immobilization or laser zona thinning. Instead, it relied on standard mechanical immobilization of the spermatozoon using the microneedle, mechanical membrane piercing and, when necessary, facilitated by aspiration of cytoplasm. The remote ICSI system was set up by an on-site operator at Hope IVF Mexico in Guadalajara. Remote operators issued commands via a digital interface to perform each of the steps detailed in Table 1; operators had control over the system and could intervene if required to correct the automation step, as well as to perform additional operations under digital control. The remote operators were located in Guadalajara (Mexico), in a room adjacent to the laboratory, and in Hudson, New York (USA), at a distance of approximately 3700 km in a straight line from the treatment centre. All injected oocytes were cultured in continuous single culture medium supplemented with human serum albumin (CSCM-C; FUJIFILM Irvine Scientific, USA), covered with oil (LifeGuard; LifeGlobal, USA) for 5 days in an 30DR Astec incubator (Fukuoka, Japan) in an atmosphere of 8.5% CO2, 5% O2, balanced with nitrogen. Blastocysts were evaluated morphologically using the AI tool ERICA (Chavez-Badiola et al., 2020). ERICA does not use time-lapse images, and instead uses a single static image. One blastocyst obtained from remote ICSI was transferred in the fresh cycle. The remaining good-quality blastocysts were vitrified following the standard Cryotop approach (Kitazato).

Embryo transferEndometrial preparation of the recipient began on day 3 of menstrual flow with 4 mg oral oestradiol (Primogyn; Schering AG, Colombia). Scans were performed to assess whether endometrial thickness equalled or exceeded 8 mm prior to initiating progesterone treatment, which involved administering 400 mg of vaginal progesterone (Geslutin; Asofarma) every 12 h starting on cycle day 15. Both medications were maintained until the pregnancy test. In the frozen embryo transfer, a day 5 blastocyst produced by remote ICSI was warmed 4 h before transfer using thawing media (Kitazato). Laser-assisted hatching was performed after warming on a spot not associated with the original area thinned during ICSI. Blood β-human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG) measurements were taken 7 days after transfer, with a concentration ≥25 IU/ml considered positive, and an ultrasound scan was performed at 6 weeks.

Results

Digital control and remote supervision of the automated ICSI system were delivered successfully. Of the 115 steps performed with the system (23 steps per oocyte), the rate of digital intervention was 49.6% (n = 57/115), with the remaining steps completed autonomously by the system, with a single exception where an on-site operator assisted in repositioning one of the oocytes. The mean time taken to identify and stabilize an oocyte on a holding pipette and prepare it for injection by laser zona thinning was 1 min 39 s. The average time for sperm selection, laser immobilization and pick-up was 3 min 50 s. The average time to deliver piezo-assisted sperm injection and release the oocyte was 4 min 38 s. Overall, the entire procedure took an average of 9 min 56 s per oocyte. During the manual procedure, the average time for sperm selection, mechanical immobilization and pick-up was 40 s. The average time to perform sperm injection and release the oocyte was 42 s. The total average per oocyte was 1 min and 22 s.

Fertilization and blastocyst formation rates were satisfactory, with four injected oocytes achieving normal fertilization in the remote ICSI group (80%, n = 4/5), compared with three oocytes in the control group where ICSI was performed manually using the standard protocol (100%, n = 3/3). Following embryo culture, two usable blastocysts were produced by remote ICSI and an additional two usable blastocysts were produced in the control group. All but one of the embryos were vitrified. ERICA AI was used to rank the embryos. A fresh embryo transfer with the remote ICSI blastocyst (Figure 2A) which had the highest ERICA ranking did not lead to pregnancy. However, a successive transfer with a vitrified-warmed remote ICSI blastocyst (Figure 2B) with the second highest ranking resulted in a blood β-HCG concentration of 61 mIU/ml on cycle day 25. The remote ICSI procedure for this blastocyst was conducted in Hudson, New York (USA), approximately 3700 km away from the gametes and IVF laboratory. An ultrasound scan performed in week 6 of pregnancy confirmed the presence of a single gestational sac with a fetal heartbeat (Figure 2C). The pregnancy continued uneventfully, with normal fetal growth. No complications were reported during delivery through elective caesarean section, which resulted in the delivery of a healthy male child at 38 weeks of gestation (weight 3.3 kg, height 50 cm, Apgar score 9). A further two blastocysts obtained in the control group remain cryopreserved at the time of writing.

Figure 2 Fresh transfer of a good-quality blastocyst produced by remote intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) (A) did not result in pregnancy. A cryopreserved blastocyst produced by remote ICSI re-expanded within 4 h after warming (B) resulted in a clinical pregnancy after assisted hatching and embryo transfer (C).

Discussion

This study reports the first successful clinical application of a fully automated, digitally controlled, remotely operated ICSI system. This system executes 23 distinct steps that comprise the entire micromanipulation part of the ICSI procedure, leading to achievement of the first live birth. Interventions from on-site operators were limited to the initial system set-up (including microtool placement). This approach differs from related efforts to reduce hands-on time for ICSI, such as microfabricated devices (McLennan et al., 2024). Additionally, the current system advances previous work (Costa-Borges et al., 2023) by automating all micromanipulation steps of the ICSI workflow, rather than selected aspects of the procedure.

The use of a sperm selection AI (SiD) provided additional advantages, as shown in previous clinical studies (Mendizabal-Ruiz et al., 2022; Montjean et al., 2024). Sperm selection by SiD was coupled with immobilization commands in a single step. Computer vision allowed visualization and accurate identification of the sperm head and tail, zona pellucida, oolemma and position of the needle inside the ooplasm. The position of microtools and the microtool tip were also determined by the AI.

The number of human operators (remote and on-site) involved in this treatment exceeded the norm, as engineers had to collaborate with embryologists. Additionally, the system took longer to complete the routine (almost 10 min per oocyte) compared with manual ICSI. However, this is expected to improve as the system becomes fully autonomous and requires significantly less supervision. Notably, digital operators do not need to possess significant previous micromanipulation experience, widening applicability. Whether or not full autonomy can be achieved will depend on the safe performance of the system without human intervention and in large case series, but even a fully autonomous system will require human supervision by on-site operators who could be supported by a remote operator. The system also requires a broadband internet connection with upload and download speeds ≥50 Mbps. Latency or delayed reaction represents a small but noteworthy risk of this procedure.

Variability in technique is inherent to microsurgery, whether on humans or embryos, influenced by changing circumstances. These variations are related to different oocyte and sperm characteristics and patient profiles, technical inconsistencies in microtool fabrication, and differences between product lots such as mineral oil and culture medium, and other unexpected variables. It remains to be determined whether the proposed automated system can be fully optimized to adapt to diverse challenges encountered during ICSI. Human oversight is expected to play a critical role in this process, facilitated through the digital control interface outlined in this study. Preliminary tests have demonstrated the feasibility of remote digital supervision by controlling the system via an internet connection. However, further refinements will be required to optimize this aspect and ensure seamless integration of human and automated workflows. The likelihood that regulators will mandate human oversight when implementing AI or automation in clinical decision-making and procedures is high, as highlighted by Zhang et al. (2024).

The step-by-step ICSI protocols developed by the authors were based on established protocols reported in the literature with some modifications. In this study, spermatozoa were immobilized using a laser rather than the standard mechanical approach. This decision was facilitated by the integration of AI-mediated sperm selection and a robotic microscope stage, which enabled the system to track the spermatozoon as it moved and centre it near the laser focus point. An algorithm then segmented the spermatozoon, allowing the laser to target the mid-point of the tail precisely for immobilization.

Laser-assisted sperm immobilization has been shown to produce comparable outcomes with mechanical methods. The first application of a 1.48-μm wavelength laser for human sperm immobilization in the context of ICSI was reported in the early 2000s. Montag et al. (2000) evaluated two strategies for laser-assisted immobilization – single and double laser shots – and demonstrated that injection of laser-immobilized spermatozoa into mouse oocytes resulted in successful activation and pronuclear formation. Subsequent studies have further supported the efficacy of laser-assisted methods. Ebner et al. (2001) conducted a prospective study and found no significant differences in fertilization rates, early cleavage or blastocyst formation between human spermatozoa immobilized using a laser and those immobilized mechanically. This finding was corroborated by Debrock et al. (2003), who similarly reported no differences in key embryological outcomes between the two immobilization methods. Notably, Ebner et al. (2002) were the first to report a live birth resulting from ICSI using spermatozoa immobilized with two successive laser shots, an approach comparable with that employed in the present study. These findings, combined with the precise and automated nature of laser-assisted immobilization, underscore the feasibility and potential advantages of this method within automated ICSI workflows.

Another deviation from the routine manual ICSI protocol was the thinning of the outer zona pellucida using a single laser shot. This approach was chosen to reduce the mechanical resistance encountered during microneedle penetration of the zona pellucida, thereby minimizing tension on the oolemma. This reduction in zona resistance is critical in maintaining oocyte integrity and avoiding unnecessary mechanical stress, which could compromise developmental competence or lead to degeneration. Moser et al. (2004) demonstrated reduced degeneration of oocytes after ICSI using a similar approach. Piezo-assisted zona penetration was not employed in this study because a standard bevelled microneedle was used. Bevelled needles are less suited for piezo-mediated zona piercing and sperm immobilization due to their geometry, but are highly effective for precise oolemma penetration. This deliberate choice ensured that the key objectives of reducing mechanical stress and maximizing efficiency during sperm injection were met while maintaining compatibility with the selected instrumentation.

While current limitations, such as operator involvement and procedure time, exist, these challenges are expected to diminish with further advancements in autonomy. This work marks a sizable step towards automation of the IVF laboratory, which could significantly and positively impact the accessibility and efficiency of ART.

Acknowledgments

Author contributionsGerardo Mendizabal-Ruiz: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methods, supervision, validation, writing – review and editing. Alejandro Chavez-Badiola: conceptualization, methods, supervision, writing – review and editing. Estefanía Hernández-Morales: investigation, methods, software, validation. Roberto Valencia-Murillo: methods, software, validation. Vladimir Ocegueda-Hernández: methods, software, validation. Nuno Costa-Borges: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methods, supervision, validation, writing – review and editing. Enric Mestres: investigation, methods, validation. Mónica Acacio: investigation, methods, validation. Queralt Matia-Algué: data curation, investigation, methods, validation. Adolfo Flores-Saiffe Farías: conceptualization, data curation, methods, project administration, supervision, validation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. David Salvador Martinez Carreon: investigation, methods. Carla Barragan: data curation, methods, project administration, validation, visualization. Giuseppe Silvestri: data curation, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Amaranta Martinez-Alvarado: investigation. Luis Miguel Campos Olmedo: investigation. Aleska Valadez Aguilar: investigation. Dante Josué Sánchez-González: investigation. Alan Murray: conceptualization, supervision. Mina Alikani: conceptualization, methods, supervision, validation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Jacques Cohen: conceptualization, methods, data curation, investigation, project administration, supervision, validation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processDuring the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT V4o to assist with copyediting. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed, and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Appendix Supplementary Materials (2)

-

References

Abdelmassih, S. ∙ Cardoso, J. ∙ Abdelmassih, V. ...

Laser-assisted ICSI: a novel approach to obtain higher oocyte survival and embryo quality rates Hum. Reprod. 2002; 17:2694-2699

Abdullah, K.A.L. ∙ Atazhanova, T. ∙ Chavez-Badiola, A. ...

Automation in ART: paving the way for the future of infertility treatment

Reprod. Sci. 2023; 30:1006-1016

Alikani, M.

The success of ICSIA and the tough road to automation

Reprod. BioMed. Online. 2023; 47, 103244

Chavez-Badiola, A. ∙ Flores-Saiffe-Farías, A. ∙ Mendizabal-Ruiz, G. ...

Embryo Ranking Intelligent Classification Algorithm (ERICA): artificial intelligence clinical assistant predicting embryo ploidy and implantation

Reprod. Biomed. Online. 2020; 41:585-593

Costa-Borges, N. ∙ Farías, A.F.S. ∙ Mendizabal, G. ...

Laser immobilization of spermatozoa for intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI): an exploratory and safety study in the mouse model

Fertil. Steril. 2024; 12:e342

Costa-Borges, N. ∙ Munné, S. ∙ Albó, E. ...

First babies conceived with automated intracytoplasmic sperm injection

Reprod. BioMed. Online. 2023; 47, 103237

Debrock, S. ∙ Spiessens, C. ∙ Afschrift, H. ...

Application of the Fertilase-laser system versus the conventional mechanical method to immobilize spermatozoa for intracytoplasmic sperm injection. A randomized controlled trial

Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2003; 56:102-105

Ebner, T. ∙ Yaman, C. ∙ Moser, M. ...

Laser assisted immobilization of spermatozoa prior to intracytoplasmic sperm injection in humans

Hum. Reprod. 2001; 16:2628-2631

Ebner, T. ∙ Moser, M. ∙ Yaman, C. ...

Successful birth after laser assisted immobilization of spermatozoa before intracytoplasmic injection

Fertil Steril. 2002; 78:417-418

Flores Saiffe Farías, A. ∙ López, Á.E.Á. ∙ Hernandez, E.G. ...

A preliminary evaluation of an artificial intelligence (AI)-driven robotic system for oocyte retrieval and denudation

Fertil. Steril. 2024; 122:e152

Gvakharia, M.O. ∙ Lipshultz, L.I. ∙ Lamb, D.J.

Human sperm microinjection into hamster oocytes: a new tool for training and evaluation of the technical proficiency of intracytoplasmic sperm injection

Fertil Steril. 2000; 73:395-401

Leung, C. ∙ Lu, Z. ∙ Esfandiari, N. ...

Automated sperm immobilization for intracytoplasmic sperm injection

IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2010; 58:935-942

Lu, Z. ∙ Zhang, X. ∙ Leung, C. ...

Robotic ICSI (intracytoplasmic sperm injection)

IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2011; 58:2102-2108

McLennan, H.J. ∙ Heinrich, S.L. ∙ Inge, M.P. ...

A micro-fabricated device (microICSI) improves porcine blastocyst development and procedural efficiency for both porcine intracytoplasmic sperm injection and human microinjection

J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2024; 41:297-309

Mendizabal-Ruiz, G. ∙ Chavez-Badiola, A. ∙ Figueroa, I.A. ...

Computer software (SiD) assisted real-time single sperm selection associated with fertilization and blastocyst formation

Reprod. BioMed. Online. 2022; 45:703-711

Mendizabal-Ruiz, G. ∙ Cohen, J. ∙ Costa-Borges, N. ...

Far away so close: remote ICSI using an AI-powered robot

Hum. Reprod. 2024; 39 deae108-218

Mendizabal-Ruiz, Gerardo ∙ Hernandez, E.G. ∙ Barragan, C.P. ...

A novel intelligent robotic micromanipulation system enables remote ICSI procedures

Fertil. Steril. 2024; 122:e354

Millan, C. ∙ Parra, A.A.P. ∙ Mendizabal, G. ...

Development and preliminary testing of a fully automated semen preparation robot

Fertil. Steril. 2024; 122:e122

Montag, M. ∙ Rink, K. ∙ Delacrétaz, G. ...

Laser-induced immobilization and plasma membrane permeabilization in human spermatozoa

Hum Reprod. 2000; 15:846-852

Montjean, D. ∙ Godin Pagé, M.-H. ∙ Pacios, C. ...

Automated Single-Sperm Selection Software (SiD) during ICSI: A Prospective Sibling Oocyte Evaluation

Med. Sci. 2024; 12:19

Moser, M. ∙ Ebner, T. ∙ Sommergruber, M. ...

Laser-assisted zona pellucida thinning prior to routine ICSI

Hum Reprod. 2004; 19:573-578

Murphy, A. ∙ Lapczynski, M.S. ∙ Proctor, Jr, G. ...

Comparison of embryologist stress, somatization, and burnout reported by embryologists working in UK HFEA-licensed ART/IVF clinics and USA ART/IVF clinics

Hum. Reprod. 2024; 39:2297-2304

Nagy, Z. ∙ Liu, J. ∙ Joris, H. ...

Andrology: The result of intracytoplasmic sperm injection is not related to any of the three basic sperm parameters

Hum. Reprod. 1995; 10:1123-1129

Palermo, G. ∙ Joris, H. ∙ Devroey, P. ...

Pregnancies after intracytoplasmic injection of single spermatozoon into an oocyte

The Lancet. 1992; 340:17-18

Tiegs, A.W. ∙ Scott, R.T.

Evaluation of fertilization, usable blastocyst development and sustained implantation rates according to intracytoplasmic sperm injection operator experience

Reprod. BioMed. Online. 2020; 41:19-27

Verza, S. ∙ Schneider, D. ∙ Siqueira, S. ...

Laser-assisted intracytoplasmic sperm injection (LA-ICSI) is safe and less traumatic than conventional ICSI

Fertil. Steril. 2013; 100:S236

Zander-Fox, D. ∙ Lam, K. ∙ Pacella-Ince, L. ...

PIEZO-ICSI increases fertilization rates compared with standard ICSI: a prospective cohort study

Reprod. BioMed. Online. 2021; 43:404-412

Zhang, S. ∙ Yu, J. ∙ Xu, X. ...

Rethinking Human-AI Collaboration in Complex Medical Decision Making: A Case Study in Sepsis Diagnosis

CHI '24: Proceedings of the 2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 445

2024

Key message

This article describes an automated workstation delivering all micromanipulation elements of intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) autonomously or under digital control, while allowing for remote operation and supervision. Its use led to the first successful remote-operator ICSI, resulting in a live birth. This work advances the automation and standardization of fertility laboratories.